The Future of College Admissions

umbers don’t lie. And when it comes to the future of admissions for higher education, they reveal a challenging reality. According to the Hechinger Report, the United States is facing a looming enrollment cliff, in which there is a dramatic drop in the number of high school seniors beginning in the fall of 2025. According to the US National Center for Health Statistics, the total birth rate has remained below the level of replacement since 2007 and continues to fall. By 2039, higher ed consulting firm Ruffalo Noel Levitz estimates that there will be 650,000, or 15 percent, fewer 18-year-olds per year than there are now. This year’s graduating cohort is the last large one before the implications of this decline take their toll not only on college admissions but on the labor force and general economy.

The Future of College Admissions

umbers don’t lie. And when it comes to the future of admissions for higher education, they reveal a challenging reality. According to the Hechinger Report, the United States is facing a looming enrollment cliff, in which there is a dramatic drop in the number of high school seniors beginning in the fall of 2025. According to the US National Center for Health Statistics, the total birth rate has remained below the level of replacement since 2007 and continues to fall. By 2039, higher ed consulting firm Ruffalo Noel Levitz estimates that there will be 650,000, or 15 percent, fewer 18-year-olds per year than there are now. This year’s graduating cohort is the last large one before the implications of this decline take their toll not only on college admissions but on the labor force and general economy.

Numerous Penn GSE alumni work in the field, both in admissions and college counseling offices, but none of the alumni we spoke with are as pessimistic about the future as those numbers would have you believe.

Approaching the “Demographic Cliff”

Leykia Nulan, GED’09, associate dean of admission and director of access initiatives and partnerships at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, concurs. “We’ve been talking about this for many, many years now,” she laughed, “probably since 2018 when Nathan Grawe released Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education. I can assure you that hundreds of thousands of dollars were spent in efforts across America to combat what we saw as this gloomy warning that there were going to be massive school closures and a fairly bleak future for a lot of small private schools.”

Nulan thinks that what has panned out is what was predicted—small school closures from tuition-driven institutions—but many schools, especially the more selective ones, have been somewhat insulated from the fallout. The Northeast, according to Conine, has “been in a demographic decline for over a decade,” taking effect after the Great Recession. He said the same is true of the Midwest. “I think once people wrapped their heads around the South and the West being places in the country where we were going to see more births and more college-age students available, strategies on recruitment and enrollment started to shift to focus on those parts of the country.”

Demographics and geography aside, the top tier of highly selective schools, as well as the state flagship institutions, seem relatively safe from fluctuating populations. “Unfortunately, we have seen community colleges hit the hardest by the demographic cliff, and also because of COVID,” Nulan said. She added that it is going to “continue to rattle tuition-driven, small, niche schools that are not necessarily able to pivot in what they offer quickly.”

Pivoting, according to Conine, is the name of the game. He explained that Merrimack is continually assessing its expertise and the needs of students, adapting by creating new programs to meet those needs. This approach allows them to capture a larger share of the student market, even as the overall pool of students shrinks. He also shared that the team is focused on anticipating future job trends in the Northeast region and aligning campus offerings accordingly, and that over the past 10–15 years, their enrollments have actually doubled. “Just because the demographics are shifting doesn’t mean that an institution has to shrink and die,” he said.

Responding to the needs of the population it serves is clearly an important factor in maintaining and expanding a school’s reach, especially since the options for a college-bound student in the US are vast. “The nice thing about the United States is that you have a lot of choice,” said Butt. “The bad thing about the United States is that you have a lot of choice. It cuts both ways.” The challenge is to sift through all those choices and to look farther than the ‘brand names.’”

“We have this incredibly hierarchically organized college system in the United States, which is different from almost every country, with a pyramid of relatively few, very elite schools at the top and community colleges and local-serving institutions at the bottom,” said Penn GSE Associate Professor Rachel Baker, who studies college access and community college success. “That image is helpful, but problematic, because it necessarily imposes this order where some are better than others, which is not the case, but that is how people talk about it.” Students must look beyond what she describes as “this very thin sliver of students” who are all competing for the same spots at the same schools. “I would hope Americans, by and large, see the value in the smaller, more regional schools that really do cater to the needs of the local economy,” she added.

There is also the growing realization that the “college-for-all mentality,” as Baker calls it, is not the answer. “There are options that aren’t college, like bootcamp-training programs and noncredential options or microcredentials that are not on students’ radars for a number of reasons that should be,” she said. “Expanding the notion of what postsecondary training can look like seems important.”

Jamiere Abney, GRD’25, an admissions officer at Seattle University, agrees. “We’re all competing for fewer traditional-age high school students going to college,” he acknowledged. “But what that does is open the door for nontraditional students.” Adult learners are one such category, and so are those who have some college but no degree reentering the system. “You can attract people who may be at change points in their careers or life that could benefit from an education if they didn’t get one right out of high school. What is your pitch to a different community? If I’m an older person, I’m not looking for an experience. I want to know what tangible skills I am going to get,” he said.

Assessing Market Need

In the graduate space, however, according to Brent Nagamine, GED’19, director of MBA admission at the University of Washington Foster School of Business, these microcredentials provide a certain amount of competition for the advanced degree. “The folks who are administering those microcredentials say, ‘Hey, we’re giving you enough, and it’s at a more affordable [cost] and much faster pace.’ And the folks who are offering the full degree counter, ‘We’re giving you a more thorough and in-depth experience.’” Some of it is branding, he said, but there is also the risk of creating so many programs to appeal to new market segments that it is no longer financially sustainable. “These programs are not purely revenue,” he said. “They also incur expense.”

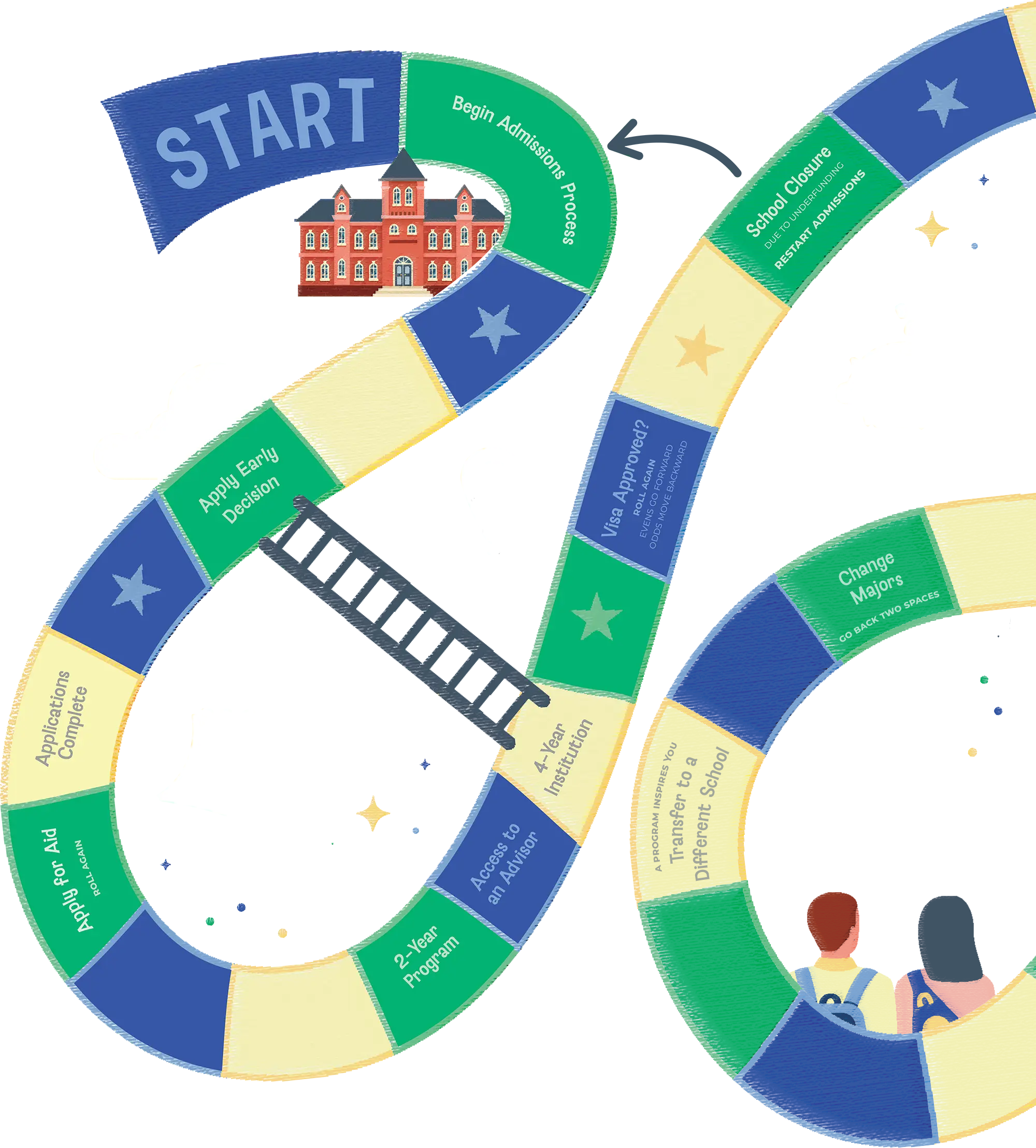

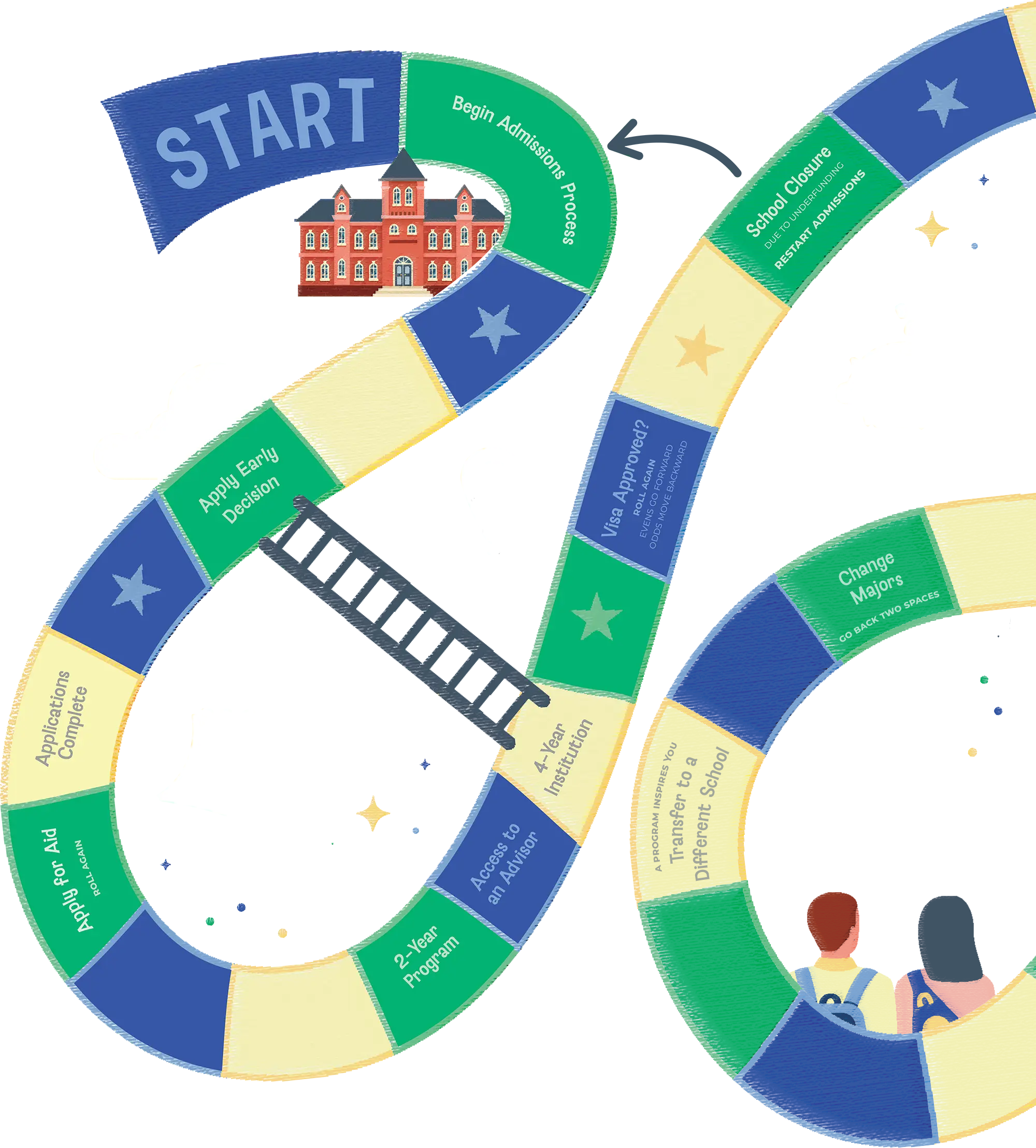

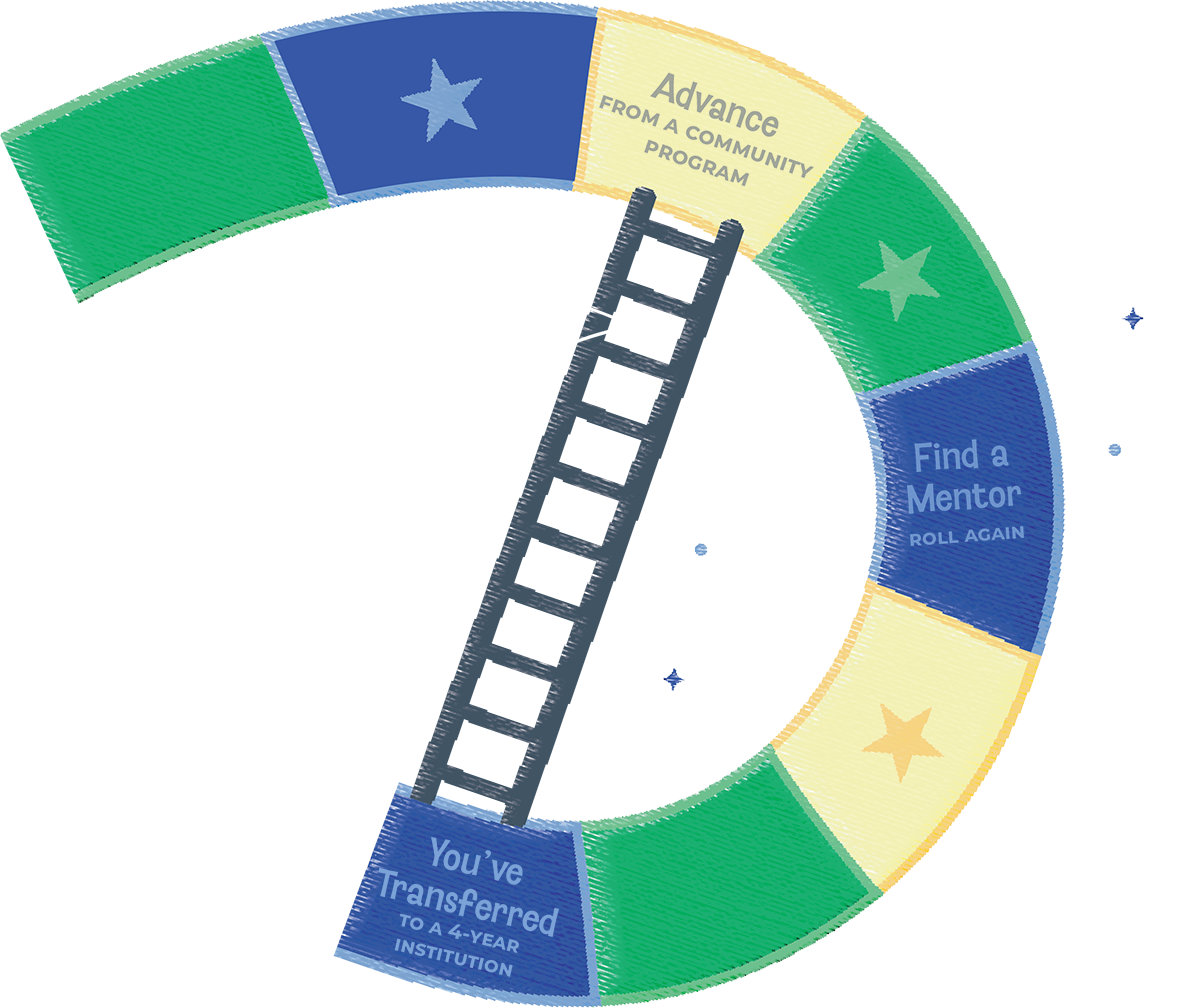

Those transferring from community colleges are another market that needs different support. “Figuring out how to transfer [from a community college] and finish that degree can be complicated and hard to navigate,” said GSE Centennial Presidential Professor and Penn’s Vice Provost for Faculty Laura Perna, C’88, W’88, who studies college access and affordability. The rate of students transferring from a two-year college to a four-year one is extremely low, according to Perna’s GSE colleague Baker, and some of that has to do with the fact that students have already obtained the credentials they need for their jobs and see no need to continue.

It’s also, Perna said, about how schools serve students. “We need to ensure that no matter where students go to college, they have access to an advisor, to a person who can support them,” she said.

The Price of Admission

The landscape is changing. Acosta said that some of the schools his students applied to in the past no longer exist, citing Birmingham-Southern College, a private liberal arts college in Alabama, and Mills College in Oakland, California.

It doesn’t help, noted Perna, that there is a lot of complexity with college costs. There is what she calls the “sticker price,” the advertised cost of attendance, versus the “net price,” the cost of attendance minus grants. “We really don’t have clear messaging many times,” she said. “Every school has a different tuition and other costs and different methods for how financial aid is determined. It’s too complicated for people to understand how much it will actually cost them to attend a particular institution. Even with the simplified FAFSA forms rolled out last year, it’s still hard. For students whose parents haven’t gone to college, it may be the student who has to take on the responsibility of figuring things out and then really making the case that college is affordable to their family.”

The Global College Market

All the admissions officers we spoke to noted that the market for international students is highly valued. “Many institutions have very global values,” Butt said. “They believe in their campuses being like the United Nations or the Olympic Village. Research would suggest that teams are better when the people on those teams are different, in whatever way you look at that.” To that end, Butt sees significant emerging markets from India, Brazil, Vietnam, Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, and Ghana. “The demand for American higher education at the undergraduate level is still very high in a lot of areas,” he said. “I think the question is more what is the investment for that family to send their student to the United States?”

The fluctuating exchange rates and the rising strength of the American dollar over the last few years have made “it even harder for our international students to be able to afford a US education,” said Nagamine. Add to that uncertainty around policy changes for international visas and the landscape is “certainly unpredictable,” said Butt. To be clear, however, said Leslie Levin, C’97, vice dean of admissions and student affairs at Penn GSE, “If there were to be more stringent restrictions, it would be to the detriment of all institutions that enroll international students.”

Despite the challenges, GSE alumni working in admissions emphasize the broader value of a college education, seeing it as more than just a financial return on investment. “It’s not just the ability to make money, but the experience and social capital that you gain in understanding how to navigate the world,” said Abney. “You learn skills and meet people through higher education in ways that aren’t just reflected in what you make in dollars and cents, but in skills that you have that you might not gain otherwise.”

The focus moving forward will need to be on making sure prospective students and their families understand this and that schools be able to adapt their approach in telling their story to them. Says Wesleyan’s Nulan: “There’s not going to be a single lever that would save all of the schools out there. . . . And I think, for that reason, the only strategy you can rely on is pivoting to offer what you think speaks to the audience that wants to hear from you.”