The Mental Health Crisis in Schools

n the Tuesday after Labor Day, Eric Brown, GED’16, a school counselor, welcomed students back to Horatio B. Hackett Elementary School in Philadelphia’s Fishtown neighborhood. “There are some students who are new to the community, and some whom I am reconnecting with,” he said. “I hang out with them during lunch and recess and visit them during art class or music.

“I want to make sure they know that support is available to them,” he said.

Even before the pandemic, he saw students of all ages struggling with mental health issues. “For some of them it’s just school stuff, grades,” he said. “I saw fourth and fifth graders spiraling over politics and elections.”

But since the pandemic, more of his students have suffered from other mental health conditions, especially anxiety. “We get self-reports from young kids about the fear of the unknown and what is coming next,” he said. “Last school year, I had two students who were having these debilitating panic attacks multiple times a week.” He also has numerous students who have lost family members, witnessed gun violence, and questioned their sexual and gender identities in recent years.

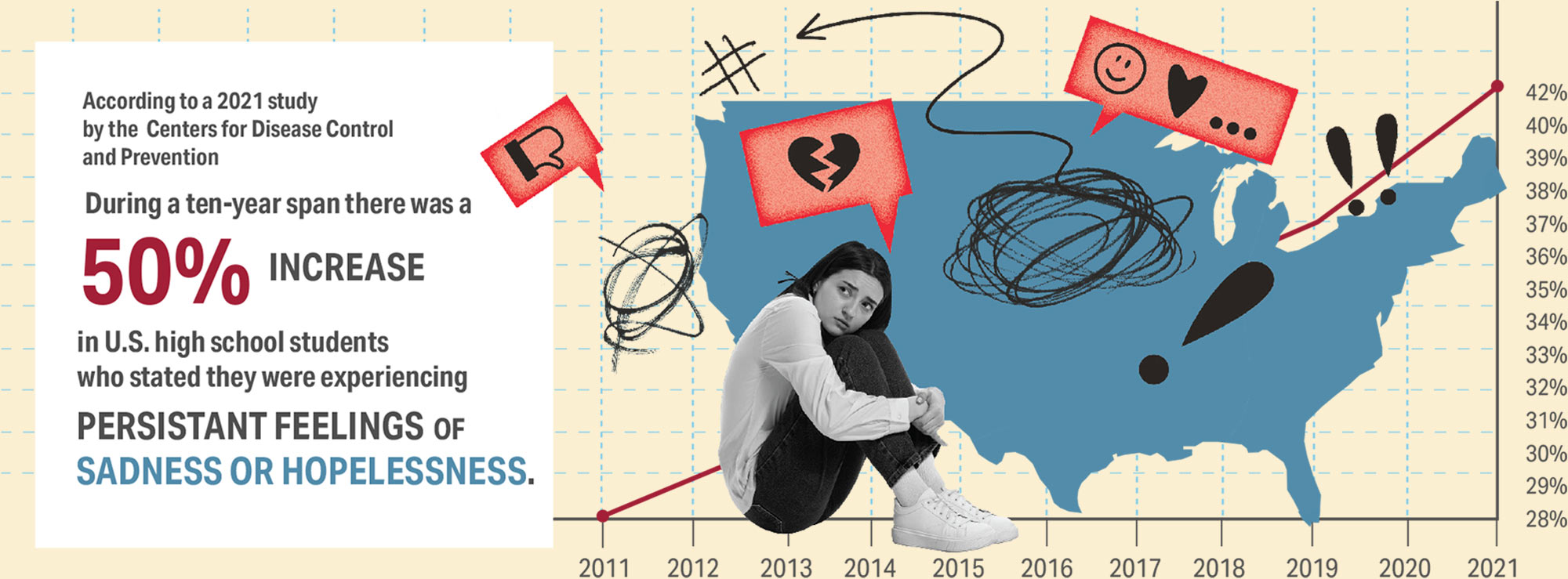

Similar challenges can be felt across the country. According to a 2021 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 42 percent of high school students said they experienced persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness during the past year. That is a 13.5 percent increase from 2019, and a 50 percent increase from a decade earlier. Additionally, 30 percent of high school girls and 45 percent of LGBTQ+ teens reported seriously considering suicide.

In May, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy released an alarming warning about the harm social media (which up to 95 percent of young people, ages 13–17, use) poses to the mental health of children and adolescents. The same month, he boldly declared that “mental health is the defining public health crisis of our time.”

Eric Brown, Hackett Elementary school counselor

As a mental health professional on the ground, Brown feels fortunate that he is in a position to help these children.

He works with small groups of elementary school students at a time, teaching them how to do breathing exercises and meditations that can distract them from anxiety. “It can be as simple as coloring a maze,” he said. “I do this meditation where I have them put a Hershey’s Kiss in their mouths and let it melt and have them reflect and meditate on it, the flavors, the texture of the chocolate. It’s amazing.”

Brown is also encouraging the school, as a whole, to make changes to help students. At the start of the day, each class now holds a community meeting where the kids, along with the teacher, discuss a fun, personal topic. “It helps build a better rapport with students and it makes these connections, so if there are issues that need to be addressed, they feel more comfortable talking about it,” said Brown.

He’s also working one-on-one with teachers to help them see the need to make time in a student’s day for addressing mental health. “The teachers have a curriculum to teach, so there is a lot of competition for time, but we are working on that,” he said. “We’re making progress.”

Brown is only one of the many Penn GSE players—students, alumni, and faculty members—who are trying to address the mental health crisis in our country’s schools. Some, like Brown, are working directly with children or adolescents. Others are trying to change things from the top, guiding educational professionals to prioritize mental health and create wellness-minded communities.

Penn GSE Professor of Practice Michael Nakkula

Photo credit: Lora Reehling Photography

Michael Nakkula, a professor at Penn GSE whose research focuses on studying the development of resilience and possibility for children and youth from low-income backgrounds, has always believed in the power of schools to address mental health challenges. “Families and students cannot consistently follow up on recommendations for outside counseling support,” he explained. “In schools, you have a chance to reach the students on a regular basis.”

Schools are also a place where you can reach all children. “All students need this type of support, not just the ones who are the most challenged,” he said. “The ones in the middle often fall between the cracks because they aren’t getting in trouble, and they aren’t the highest achievers, but they have social and emotional challenges, too.”

But if they aren’t careful, schools can also become places that exacerbate students’ mental health challenges. “The other side to this is, when there is school disengagement and isolation, students tend to feel sadder, bored, depressed, anxious, all of these negative feelings,” he said.

Individual practitioners were coping with their own mental health issues and wellness issues. We were always on the cusp of burning out, and then the pandemic happened, and we realized that the old tactics we were using to cope would no longer work.

Individual practitioners were coping with their own mental health issues and wellness issues. We were always on the cusp of burning out, and then the pandemic happened, and we realized that the old tactics we were using to cope would no longer work.

— Stacey Carlough, GED’06

To help schools make sure they are helpful, not hurtful, he and Andy Danilchick, an education consultant and Penn GSE doctoral student, launched the Project for Mental Health and Optimal Development. Based at Penn GSE, it brings together representatives from Pennsylvania school districts once a month to create and execute strategic plans for addressing mental health in their districts. Every district sends a team of approximately five participants that usually includes a teacher, a counselor, an assistant principal, and a principal. The program started in 2018 and now works with 30 Pennsylvania districts.

Every meeting starts with a training so representatives from each district can learn techniques to support students. For example, the consortium has been focusing on trauma-informed approaches to address disruptive classroom behavior. “In one of the sessions, a teacher was asking for language [to use in class], so we brainstormed ideas,” said Nakkula. “One thing that I shared was that you might not be able to calm down a student who is misbehaving in the moment, but you can say, ‘Jeremy, something is clearly bothering you. We can’t talk about it right now, but I would like to check in after class if that’s okay with you.’”

Then each district engages in a private strategic planning session to address its own particular needs. For example, one district decided what they really needed was more resources for students who need intensive support. So they used the time in the consortium to figure out how they could advocate for a children’s partial hospitalization unit in their county. “They ended up getting the resources, which was an extraordinary achievement,” said Nakkula. “They gave credit to the consortium for giving them the time and space to focus on this.”

Penn GSE also provides a liaison for each district to check in between meetings and see how their plans are going. “The reason this is so important is that the people in school districts are overwhelmed with challenges,” said Nakkula. “They have a lot on their plates.”

As the country was emerging from the pandemic, it became clear that mental health challenges were not just facing students, but the teachers, counselors, and other “helping professionals” in schools as well. “Individual practitioners were coping with their own mental health issues and wellness issues,” said Stacey Carlough, GED’06, assistant director of teaching and learning at the Penn GSE Office of School and Community Engagement (OSCE). “We were always on the cusp of burning out, and then the pandemic happened, and we realized that the old tactics we were using to cope would no longer work.”

Even before the pandemic, educators were grappling with how to prioritize self-care in a profession where burnout is all too common. Taking time off, even when it’s the responsible thing, can have unanticipated effects.

This need to strengthen individual practitioners’ as well as whole school communities’ capacity for wellness is what led Carlough, with Caroline Watts, senior lecturer and director of OSCE, to expand its Alliance for Interprofessional Education—to try and help “right this ship,” as Carlough put it.

The goal of the initiative is to build an engaged community of education professionals (including teachers, counselors, social workers, nurses, administrators, and other school-based staff) who support one another in creating and maintaining communities where wellness is sustainable. That way, the “helpers” have the skills, knowledge, and support they need to consistently show up for their students with less risk of compassion fatigue.

And it’s not about offering a one-time meditation or giving staff a coupon for a free coffee. “It’s about shifting the entire system and creating a culture where everyone is responsible for making sure everyone is focusing on wellness,” said Carlough.

Sometimes, the Alliance brings professionals together in person to learn strategies they can implement in their schools. For example, at last year’s Winter Wellness Mixer, the group invited pre-service and in-service teachers and counselors to a series of workshops. In one, a somatic bodyworker instructed educators on self-message and breathing techniques that can help lower stress levels immediately.

Last year, in another session designed for Philadelphia school leaders, participants learned how to engage in mindful communication. “Say a principal and a teacher are walking down a hallway. They might both have a lot on their minds, and so that quick conversion has the potential to leave one or both of them feeling frustrated or more stressed out. Or it can be a moment of connection, leaving them feel heard and supported,” said Carlough.

This year, the Alliance launched the New Practitioner Collaborative (NPC), a twice-daily, drop-in virtual support and co-working space for anyone volunteering, training, or working in a K–12 school. Education practitioners can pop in at their leisure to engage in thought-partnership on a professional challenge or idea. Or they can use the space to have someone hold them gently accountable for practices that reduce stress, from staying on top of grading to following through on a daily meditation goal.

“The NPC is open and staffed, and now we just need to get the message out that this is here,” said Carlough. “This is about folks who have something to give, offering to hold the space for folks who have a need. It’s a place to come and receive support, to get ideas, to have a sounding board, and to feel connected to a community that cares about the next generation of helping professionals. This isn’t just self-care or a spa day. This is the energy you get from a partnership with people who care and want you to succeed.”

Director of School and Community Engagement Caroline Watts in her classroom. Photo credit: Darryl W. Moran Photography

Penn GSE is also preparing the next generation of school counselors who will be addressing students’ mental health needs at the ground level.

OSCE’s Watts, who is also a licensed psychologist and former faculty member in the Professional Counseling program, said that Penn GSE’s counseling programs have become even more focused on addressing the impact of social injustices in the preparation of its school and mental health counselors. “We really need to have a counseling mindset that is inclusive and be able to respond to a range of individuals from a range of backgrounds and a range of identities.”

The counseling faculty have also incorporated teaching alternative therapeutic approaches so it can reach as many people as possible in the ways that work for them. “As a result of the pandemic and the increased presence of telehealth, we also train our counselors on what are the best practices at forming effective therapeutic relationships over Zoom and over the phone,” she said. “We talk about issues like: How do you set boundaries in this kind of setting? And what are the appropriate ways to handle this relationship?”

Marsha Richardson, a senior lecturer and the director of the School and Mental Health Counseling program, said in her class they focus on unique and creative ways to engage students and children through the use of technology. “One of my former students, who now teaches, created this amazing website for an elementary school where there is a cartoon character of her, and she is situated in a virtual office,” she said. “Everything you click on, whether it’s books on the shelf or a chair, opens up a link or activity to teach about mental wellness.

“It’s amazing,” she added. “I had her come to my class this year to demonstrate to students all the interactive ways they can reach people.”

Senior Lecturer Marsha Richardson meeting with Penn GSE counseling students.

Photo credit: Ryan Collerd

Penn GSE also has new initiatives to get counseling students in front of more children and in more settings. It’s a win-win—students get experience and the institutions need the help. “The national recommendation is that there should be a counselor for every 250 students,” said Brown, the alumnus who is working in Fishtown. “That low number might blow you away, but there are many schools, especially in Philadelphia, where that ratio isn’t even met. It’s more like one counselor to 400 kids.”

For the past three years, as a way to support students coming back to school in person after the pandemic, OSCE has collaborated with the Netter Center for Community Partnerships to provide increased academic and social-emotional supports for elementary students in West and Southwest Philadelphia over the summer. As part of this program, Penn GSE graduate counseling students seamlessly integrated their mental health and wellness work with the students’ academic schedule.

“Unlike previous years, we didn’t have scheduled classroom guidance lessons,” said Semaj Capers, GED’22, GED’23, a certified school counselor who worked for two summers in West Philadelphia schools. “We would attend their chess or dance or acting classes, or we would play with the kids during recess and at lunch.”

When a mental health need arose, he would step in. For example, he gave a lesson on boundaries after the third and fourth graders were being too physical in the way they were playing. “We did an activity where there were four circles, and the smallest circle was for your personal space and then it grew,” he said. “They labeled who could be in that space, and they had fun with it.”

Vicki Swanson, a second-year graduate student in the Professional Counseling program, also spent the summer as a counselor at Comegys Elementary School in Southwest Philadelphia, where the counseling office was known as the “Zen Den.” She said she felt encouraged by how excited the kids were to have adults in their lives who were just there to support their emotional health.

“They liked having a group of staff whose job wasn’t necessarily to teach them anything or make them do certain things and, instead, provide a space the students could have some agency over according to their individual needs,” she said. “Some kids would come hang on a daily basis. That’s when you can really make a difference.”